Hydrocarbon Reserves represent a cornerstone of global energy systems, fueling economies and shaping geopolitical landscapes. These reserves, encompassing crude oil, natural gas, and natural gas liquids, are finite resources formed over millions of years through complex geological processes. Understanding their formation, exploration, extraction, and environmental impact is crucial for navigating the complexities of energy security and sustainable development in the 21st century.

This exploration delves into the multifaceted world of hydrocarbon reserves, examining their significance from geological origins to their future in a rapidly evolving energy market.

From the vast oil fields of the Middle East to the shale gas formations of North America, the distribution of these reserves is uneven, leading to significant geopolitical implications. The methods used to locate, extract, and utilize these resources have evolved dramatically, with technological advancements constantly pushing the boundaries of efficiency and sustainability. However, the environmental consequences of hydrocarbon extraction remain a critical concern, prompting ongoing research into mitigation strategies and the transition towards renewable energy sources.

This exploration will examine all these aspects, providing a comprehensive understanding of this vital yet controversial resource.

Definition and Types of Hydrocarbon Reserves

Hydrocarbon reserves represent the estimated quantities of oil and natural gas that are economically and technically recoverable from known accumulations beneath the Earth’s surface. These reserves are a crucial resource for global energy production and are constantly being explored, developed, and refined in their estimation. Accurate assessment of reserves is essential for investment decisions, resource planning, and government policy-making.

Hydrocarbon Reserve Classifications

Hydrocarbon reserves are categorized based on the level of certainty associated with their recovery. This classification system helps companies and governments understand the potential for future production and manage resources effectively. The most common classifications are proven, probable, and possible reserves. The degree of certainty decreases as we move from proven to possible reserves.

Types of Hydrocarbons in Reserves

Hydrocarbon reserves primarily consist of three main types: crude oil, natural gas, and natural gas liquids (NGLs). Crude oil is a viscous, dark liquid composed of a complex mixture of hydrocarbons. Natural gas is primarily methane, a lighter hydrocarbon that exists in gaseous form under standard conditions. Natural gas liquids are a group of hydrocarbon compounds that are gaseous under standard conditions but can be liquefied under pressure and low temperatures.

These NGLs include propane, butane, and ethane, all valuable energy sources and petrochemical feedstocks.

Comparison of Hydrocarbon Reserve Types

| Type | Definition | Recovery Method | Typical Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proven Reserves | Reserves that are 90% certain to be recoverable with existing technology and current economic conditions. These reserves have already been discovered and their volume accurately estimated. | Various methods, depending on reservoir characteristics (e.g., primary, secondary, tertiary recovery). | Existing oil and gas fields, both onshore and offshore. Examples include the Ghawar field in Saudi Arabia (crude oil) and the South Pars/North Dome field (natural gas). |

| Probable Reserves | Reserves that have a 50% probability of being recoverable. Geological and engineering data suggest their existence, but further investigation might be needed for definitive confirmation. | Similar to proven reserves, but may require additional exploration or improved recovery techniques. | Newly discovered fields or extensions of existing fields requiring further appraisal. Examples might include discoveries in deepwater areas or unconventional shale formations. |

| Possible Reserves | Reserves that have a 10% probability of being recoverable. These are based on geological indications but lack sufficient data for a more certain assessment. Often associated with exploration prospects. | Requires significant further exploration and development before economic viability can be determined. | Untested exploration blocks, areas with limited geological data, or speculative extensions of known fields. Examples could be areas recently opened for exploration or frontier basins. |

Geological Formation and Location of Reserves

Hydrocarbon reserves, the accumulations of oil and natural gas, are the result of complex geological processes spanning millions of years. Understanding these processes and the geological environments where they occur is crucial for exploration and production. The location of these reserves is highly variable, influenced by the interplay of source rock maturation, migration pathways, and suitable reservoir rocks.Geological processes leading to hydrocarbon reserve formation begin with the accumulation of organic matter in sedimentary basins.

Over time, this organic matter is buried under layers of sediment, subjected to increasing pressure and temperature. This process, known as diagenesis, transforms the organic matter into kerogen. Further burial and increased heat lead to the thermal cracking of kerogen, a process called catagenesis, generating hydrocarbons – oil and natural gas. These hydrocarbons, being less dense than the surrounding water, migrate upwards through porous and permeable reservoir rocks until they encounter an impermeable cap rock, trapping them to form an accumulation, or reservoir.

The efficiency of this trapping mechanism largely determines the size and economic viability of the reserve.

Major Geological Formations Hosting Hydrocarbon Reserves

Hydrocarbon reserves are predominantly found in sedimentary basins, vast depressions filled with layers of sediment. These basins form in various tectonic settings, including continental rifts, passive margins, and foreland basins. Specific rock types within these basins act as source rocks (generating hydrocarbons), reservoir rocks (storing hydrocarbons), and cap rocks (trapping hydrocarbons). Examples include sandstone, limestone, and shale formations, each possessing unique characteristics influencing the type and quantity of hydrocarbons they can hold.

Understanding hydrocarbon reserves is crucial for energy planning. But designing efficient homes that minimize energy consumption is equally important, and that’s where exploring different design options comes in. Check out this helpful resource for comparing different AI powered home design platforms online to see how technology can help optimize energy use in your future home, ultimately impacting our reliance on hydrocarbon reserves.

The structural geology of the basin, including faults and folds, also plays a crucial role in controlling hydrocarbon migration and accumulation.

Examples of Significant Hydrocarbon Reserve Locations

The Middle East, particularly the Persian Gulf region, is renowned for its massive oil and gas reserves, largely associated with extensive carbonate and clastic sedimentary formations within the Arabian Plate. The Ghawar field in Saudi Arabia, one of the world’s largest oil fields, exemplifies this. Its geological context involves a large anticline trap within a thick sequence of Paleozoic and Mesozoic carbonate rocks.The West Siberian Basin in Russia is another prime example, containing vast reserves of oil and gas primarily within Cretaceous and Jurassic sandstone and shale formations.

The basin’s extensive size and the presence of multiple reservoir layers contribute to its significant hydrocarbon wealth. In contrast, the North Sea, while geographically smaller, showcases a different geological setting. Hydrocarbon reserves here are found in various sandstone reservoirs within fractured and faulted Mesozoic rocks, often associated with complex structural traps.

Major Global Regions and Hydrocarbon Types

The following regions are known for their significant hydrocarbon reserves:

- Middle East: Predominantly oil, with significant associated gas. Reservoirs are often large, structurally controlled traps within thick carbonate sequences.

- North America (particularly the Gulf of Mexico and Western Canada): A mix of oil and natural gas, with significant unconventional resources like shale gas and oil sands. Reservoirs are diverse, ranging from conventional sandstone and carbonate traps to unconventional shale formations.

- Russia and Central Asia: Large reserves of both oil and natural gas, with significant deposits in the West Siberian Basin and other sedimentary basins. Reservoirs are often found in sandstone and shale formations of various ages.

- South America (Venezuela and Brazil): Significant oil reserves, with Venezuela possessing substantial heavy oil deposits in the Orinoco Belt. Reservoirs are often associated with large sedimentary basins containing both conventional and unconventional resources.

- Africa (Nigeria, Libya, Algeria): Significant oil and gas reserves, with diverse geological settings and reservoir types. Many reserves are located in sedimentary basins along the northern and western coasts.

Exploration and Extraction Methods

Locating and accessing hydrocarbon reserves is a complex process involving sophisticated technology and a deep understanding of geology. Exploration focuses on identifying potential reservoirs, while extraction involves various techniques to bring the hydrocarbons to the surface. The efficiency and environmental impact of both processes are crucial considerations.

Hydrocarbon Exploration Methods

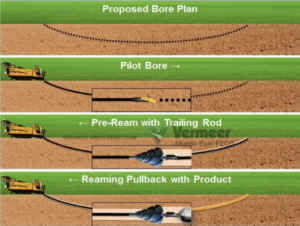

Exploration for hydrocarbon reserves begins with geological studies and analysis of existing data. This is followed by geophysical surveys, primarily seismic surveys, to map subsurface structures. Seismic surveys use sound waves to create images of rock layers beneath the Earth’s surface, revealing potential reservoir formations. These surveys can be conducted on land, at sea, or even from the air.

Following promising seismic results, exploratory drilling is undertaken to directly sample the subsurface formations and confirm the presence of hydrocarbons. Exploratory wells provide crucial information about the reservoir’s properties, including the type and quantity of hydrocarbons present, as well as the pressure and permeability of the rock formations.

Hydrocarbon Extraction Methods, Hydrocarbon Reserves

Once a commercially viable hydrocarbon reservoir is identified, the extraction process begins. This process is broadly categorized into primary, secondary, and tertiary recovery methods. Primary recovery relies on the natural pressure within the reservoir to push the hydrocarbons to the surface. This method is relatively simple and inexpensive but typically recovers only a small fraction (around 10-15%) of the total hydrocarbons in place.

Secondary recovery techniques are employed when the natural pressure declines. These methods involve injecting fluids, such as water or gas, into the reservoir to maintain pressure and displace the hydrocarbons. This can significantly increase recovery rates, often reaching 30-40%. Tertiary recovery methods, also known as enhanced oil recovery (EOR), are used to extract the remaining hydrocarbons. These techniques utilize more advanced methods such as chemical injection, thermal recovery (steam injection), or gas injection to improve the mobility of the hydrocarbons and increase recovery rates.

Tertiary recovery can push recovery rates up to 60% or more, but it’s significantly more expensive than primary or secondary methods.

Conventional vs. Unconventional Hydrocarbon Extraction

Conventional hydrocarbon extraction involves accessing reservoirs that are relatively easy to reach and produce hydrocarbons at economically viable rates. These reservoirs are typically located in permeable rock formations with sufficient pressure to allow for efficient flow. Unconventional extraction, on the other hand, targets resources that are more difficult to access and require specialized techniques. Examples include shale gas extraction through hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”), tight oil extraction, and heavy oil extraction using steam-assisted gravity drainage (SAGD).

While unconventional extraction has significantly increased hydrocarbon production, it also raises environmental concerns due to higher water usage, potential groundwater contamination, and greenhouse gas emissions.

Comparison of Hydrocarbon Extraction Methods

| Method | Advantages | Environmental Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Recovery | Simple, inexpensive, low initial investment. | Relatively low environmental impact compared to secondary and tertiary methods. However, still contributes to greenhouse gas emissions from the combustion of extracted hydrocarbons. |

| Secondary Recovery (Waterflooding) | Increases recovery rates compared to primary recovery, relatively established technology. | Moderate environmental impact. Potential for water contamination if not managed properly. Increased energy consumption compared to primary recovery. |

| Tertiary Recovery (Steam Injection) | Significantly increases recovery rates, can extract hydrocarbons from otherwise unrecoverable reservoirs. | High environmental impact. Requires significant energy input, leading to high greenhouse gas emissions. Potential for soil and water contamination. |

Reserves Estimation and Quantification

Source: biosearchambiente.it

Accurately estimating the size and quantity of hydrocarbon reserves is crucial for investment decisions, production planning, and resource management. The process is complex, involving geological interpretation, engineering analysis, and statistical methods, and is inherently uncertain due to the subsurface nature of hydrocarbon deposits. Various techniques are employed, each with its own strengths and weaknesses, often used in combination to provide a more robust estimate.

Methods for Estimating Hydrocarbon Reserves

Several methods are used to estimate hydrocarbon reserves, each relying on different data and assumptions. These methods range from simple volumetric calculations to sophisticated reservoir simulation models. The choice of method depends on the available data, the stage of field development, and the desired level of accuracy.

- Volumetric Method: This is a relatively simple method that estimates reserves based on the size of the reservoir, the porosity and hydrocarbon saturation of the rock, and the recovery factor. It requires a good understanding of the reservoir geometry and petrophysical properties. A key limitation is its reliance on assumptions about reservoir properties that may not be fully known, especially in early exploration stages.

Vast hydrocarbon reserves lie beneath the ocean floor, requiring specialized equipment for extraction. These reserves are accessed using structures like an Oil Rig , which is essentially a floating or fixed platform designed for drilling and production. The efficiency of these rigs directly impacts the rate at which we can tap into these crucial hydrocarbon reserves, influencing global energy markets.

For example, estimating the recoverable reserves of a newly discovered oil field might initially rely on volumetric calculations using seismic data and well logs, but these estimates will be refined as more data becomes available through drilling and production testing.

- Material Balance Method: This method uses pressure and production data to estimate the original hydrocarbon in place and the remaining reserves. It is particularly useful for mature fields where extensive production history is available. However, it requires accurate pressure and production data, and its accuracy depends on the validity of the underlying reservoir model. For instance, a mature gas field with a long history of production can use this method to assess remaining reserves, factoring in pressure decline and production rates over time.

- Analogous Field Method: This method uses data from similar fields to estimate reserves in a new field. It relies on the assumption that the new field shares similar geological characteristics and production behavior with the analogous field. This approach is useful in early exploration stages when limited data is available, but its accuracy depends on the similarity between the fields. A newly discovered oil field might be compared to a similar field in the same basin to estimate potential reserves, relying on geological similarities and production history of the analog.

- Reservoir Simulation: This is a sophisticated method that uses numerical models to simulate fluid flow in the reservoir. It incorporates detailed geological and engineering data to predict reservoir performance and estimate reserves. It provides a more comprehensive and accurate estimate than simpler methods but requires significant computational resources and expertise. Large-scale oil and gas fields often use reservoir simulation to optimize production strategies and refine reserve estimates over time, taking into account factors like pressure depletion, water influx, and changes in reservoir permeability.

Uncertainties and Challenges in Reserve Quantification

Accurately quantifying hydrocarbon reserves is challenging due to several inherent uncertainties:

- Geological Uncertainty: The subsurface geology is often complex and poorly understood, leading to uncertainty in reservoir geometry, porosity, permeability, and fluid saturation.

- Technological Uncertainty: Advances in drilling and production technologies can impact the recovery factor, leading to revisions in reserve estimates.

- Economic Uncertainty: Changes in oil and gas prices, operating costs, and regulatory environment can affect the economic viability of a project and hence the definition of reserves.

- Data Limitations: The available data is often limited, especially in early exploration stages, leading to significant uncertainty in reserve estimates. Seismic surveys and well logs provide valuable information, but they are indirect measurements and subject to interpretation.

Flowchart Illustrating Hydrocarbon Reserve Estimation

[Start] --> [Data Acquisition (Seismic, Well Logs, Core Data)] --> [Geological Interpretation (Reservoir Geometry, Petrophysical Properties)] --> [Reserve Estimation Method Selection (Volumetric, Material Balance, Analogous Field, Simulation)] --> [Reserve Calculation] --> [Uncertainty Analysis] --> [Reserve Reporting (Proved, Probable, Possible)] --> [End]

Economic and Geopolitical Significance

Hydrocarbon reserves, encompassing oil and natural gas, are cornerstones of the global economy and wield significant geopolitical influence. Their economic importance stems from their role as primary energy sources fueling industries, transportation, and households worldwide, while their geopolitical implications are deeply intertwined with national security, international relations, and power dynamics. The control and distribution of these resources have historically shaped alliances, conflicts, and the very fabric of international politics.

The economic importance of hydrocarbon reserves is undeniable. Nations rich in these resources often enjoy substantial revenue streams from production and export, driving economic growth and development. This revenue can fund public services, infrastructure projects, and social programs. However, dependence on hydrocarbon revenues can also create vulnerabilities, making economies susceptible to price fluctuations and global market shifts.

Hydrocarbon reserves are crucial for energy production, but accessing them requires sophisticated techniques. The process often begins with drilling, and you can learn more about the various methods involved at Drilling. Efficient and safe drilling operations are essential for maximizing the extraction of these valuable reserves, ensuring a steady supply of energy resources for the future.

For global markets, hydrocarbons represent a fundamental commodity influencing inflation, trade balances, and the overall health of national and international economies. The price of oil, for example, acts as a significant barometer for global economic health, often impacting investment decisions and consumer spending.

Understanding hydrocarbon reserves is crucial for energy security. Locating these reserves often involves extensive and risky work, which is why the process of Oil Exploration is so vital. Successful exploration directly impacts the size and accessibility of future hydrocarbon reserves, influencing global energy markets and pricing.

Economic Importance of Hydrocarbon Reserves

Hydrocarbon reserves are crucial drivers of national and global economies. Countries with significant reserves often see a considerable boost to their GDP through export revenues, taxation, and employment opportunities within the energy sector. This wealth can be channeled into development initiatives, such as infrastructure improvements, healthcare, and education. However, the “resource curse” is a phenomenon where an overreliance on hydrocarbon revenues can lead to economic instability, corruption, and a lack of diversification in other sectors.

Understanding hydrocarbon reserves is crucial for energy security. Locating these reserves often begins with drilling an exploration well, like those detailed on this site: Exploration Well. The data gathered from these wells helps geologists assess the size and viability of potential hydrocarbon deposits, ultimately informing future extraction plans and resource management.

For example, some oil-rich nations have seen their economies struggle to adapt when oil prices decline, highlighting the need for strategic economic diversification. The global market relies heavily on a stable supply of hydrocarbons, and disruptions to this supply, whether due to geopolitical instability or natural disasters, can have significant ripple effects on global prices and economic activity.

Geopolitical Implications of Hydrocarbon Reserves

Control over hydrocarbon reserves is a major factor influencing international relations and energy security. Nations with abundant reserves often wield considerable political leverage, shaping global energy markets and influencing foreign policy decisions of other countries. Energy security, the ability of a nation to access reliable and affordable energy supplies, is a critical national security concern, driving countries to secure access to hydrocarbon resources through various means, including diplomatic negotiations, strategic alliances, and even military intervention.

The competition for these resources can lead to geopolitical tensions, conflicts, and the formation of strategic partnerships aimed at securing access to and control over energy supplies.

Case Studies Illustrating Geopolitical Impact

The influence of hydrocarbon reserves on geopolitical dynamics is clearly demonstrated in several historical and contemporary examples.

- The Persian Gulf Region: The concentration of vast oil reserves in the Persian Gulf has made it a focal point of global geopolitics for decades. Competition for control over these resources has led to numerous conflicts, shaped regional alliances, and influenced the foreign policy of major global powers. The region’s strategic importance has led to significant military presence and ongoing geopolitical tensions.

Understanding hydrocarbon reserves is crucial for energy planning. Visualizing potential infrastructure, like pipelines or processing plants, is greatly aided by advanced technology; for instance, check out AI tools for creating realistic 3D models of home designs online – imagine the possibilities for scaling that to industrial projects! This kind of detailed modeling helps optimize hydrocarbon reserve management and minimizes environmental impact.

- Russia and its Gas Exports: Russia’s substantial natural gas reserves give it considerable leverage over European energy markets. This has been used as a tool in diplomatic negotiations and has at times created significant dependence and vulnerabilities for European nations. The Nord Stream pipeline, for instance, exemplifies the geopolitical implications of energy infrastructure projects.

- Venezuela’s Oil and Political Instability: Venezuela, once a major oil exporter, has experienced significant political and economic instability, partly due to the mismanagement and volatility associated with its dependence on oil revenues. The struggle for control over the country’s oil resources has contributed to internal conflicts and its complex relationship with other nations.

Environmental Impact of Hydrocarbon Extraction

The extraction of hydrocarbons, while crucial to modern society, carries significant environmental consequences. These impacts span a wide range, from greenhouse gas emissions contributing to climate change to the disruption of delicate ecosystems and contamination of vital water resources. Understanding these impacts and implementing effective mitigation strategies is paramount for responsible energy production.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions

The combustion of extracted hydrocarbons—oil, natural gas, and coal—releases large quantities of greenhouse gases (GHGs), primarily carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O), into the atmosphere. These gases trap heat, leading to global warming and climate change. The magnitude of these emissions varies depending on the type of hydrocarbon and the extraction method. For instance, the extraction and processing of unconventional gas resources like shale gas often release more methane than conventional natural gas extraction.

Furthermore, fugitive emissions, which are unintentional releases during the extraction, processing, and transportation of hydrocarbons, contribute significantly to the overall GHG footprint. Mitigation strategies include improving extraction techniques to minimize methane leakage, investing in carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies, and transitioning towards renewable energy sources.

Habitat Destruction and Land Degradation

Hydrocarbon extraction activities often lead to significant habitat destruction and land degradation. Exploration and drilling operations require extensive land clearing and infrastructure development, resulting in the loss of biodiversity and the disruption of natural ecosystems. For example, offshore oil and gas platforms can disrupt marine habitats, while onshore drilling can fragment forests and other terrestrial ecosystems. The construction of pipelines and roads further exacerbates habitat fragmentation and increases the risk of soil erosion and water pollution.

Mitigation strategies include minimizing land disturbance through improved planning and technology, implementing habitat restoration programs, and utilizing existing infrastructure whenever possible. Careful site selection and environmental impact assessments can also help reduce the overall impact on ecosystems.

Water Pollution

Hydrocarbon extraction can lead to significant water pollution, affecting both surface and groundwater resources. Spills during extraction, transportation, and processing can contaminate water bodies with oil and other harmful chemicals. Furthermore, wastewater generated during hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) often contains high concentrations of salts, heavy metals, and radioactive materials. This wastewater can contaminate groundwater sources if not properly managed.

In addition, the extraction process itself can deplete groundwater resources, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions. Mitigation strategies include implementing stringent safety regulations and spill prevention measures, treating wastewater before disposal or reuse, and carefully managing groundwater resources to prevent depletion. Regular monitoring of water quality is also crucial for detecting and addressing potential pollution incidents.

Significant Environmental Consequences and Potential Solutions

| Environmental Consequence | Detailed Explanation | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Climate Change due to GHG Emissions | The burning of fossil fuels releases large amounts of greenhouse gases, primarily CO2, contributing significantly to global warming and its associated effects like sea-level rise, extreme weather events, and disruptions to ecosystems. Methane leaks during extraction also exacerbate the problem. | Transition to renewable energy sources (solar, wind, geothermal), improve energy efficiency, develop and deploy carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies, reduce methane emissions from extraction and transportation, promote sustainable land management practices. |

| Habitat Loss and Biodiversity Reduction | Exploration and extraction activities, including deforestation, road construction, and pipeline installation, directly destroy habitats and fragment landscapes, leading to loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services. Offshore drilling impacts marine ecosystems. | Careful site selection and environmental impact assessments, minimize land disturbance, implement habitat restoration programs, utilize existing infrastructure, protect endangered species, promote sustainable forestry practices. |

| Water Contamination | Spills, leaks, and wastewater from extraction operations can contaminate surface and groundwater with oil, heavy metals, and other harmful chemicals. Fracking wastewater is a particular concern. | Implement stringent safety regulations and spill prevention measures, treat wastewater before disposal or reuse, monitor water quality regularly, develop and implement responsible water management plans, utilize closed-loop water systems in fracking operations. |

Future of Hydrocarbon Reserves

The future of hydrocarbon reserves is inextricably linked to the global energy transition and the increasing urgency to mitigate climate change. While demand for hydrocarbons remains significant, particularly in developing nations, the long-term outlook is characterized by a gradual decline in their dominance as renewable energy sources gain traction. This shift necessitates a careful examination of depletion rates, technological advancements, and the evolving geopolitical landscape.

Depletion Rates and the Transition to Renewable Energy Sources: Current consumption rates, coupled with the finite nature of fossil fuel reserves, suggest a gradual decline in their availability. The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects a significant decrease in the share of hydrocarbons in the global energy mix by 2050, even under scenarios with continued hydrocarbon use. This transition is driven by ambitious climate targets, stricter environmental regulations, and the increasing economic competitiveness of renewable energy technologies like solar and wind power.

However, the speed of this transition varies significantly across regions, with developing economies potentially relying on hydrocarbons for a longer period to meet their energy demands.

Technological Advancements Extending Hydrocarbon Reserve Lifespan

Technological innovations play a crucial role in maximizing the extraction and utilization of existing hydrocarbon reserves. Enhanced oil recovery (EOR) techniques, such as steam injection and CO2 injection, significantly improve the extraction efficiency from mature fields. Horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (fracking) have unlocked previously inaccessible reserves of shale gas and oil, extending the productive life of certain basins.

Understanding hydrocarbon reserves is crucial for energy security. A significant portion of these reserves comes from natural gas, and exploring for these resources is a complex process. To learn more about the methods and challenges involved, check out this informative page on Gas Exploration. Ultimately, successful gas exploration directly impacts the overall size and accessibility of global hydrocarbon reserves.

Further advancements in carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technologies aim to reduce the environmental impact of hydrocarbon combustion, potentially allowing for continued hydrocarbon use in a more sustainable manner. For instance, the Sleipner project in the North Sea demonstrates the feasibility of capturing CO2 from natural gas production and storing it underground.

Challenges and Opportunities Related to the Future of Hydrocarbon Reserves

The future of hydrocarbon reserves presents both challenges and opportunities. Challenges include managing the environmental impact of extraction, ensuring energy security in a transitioning energy landscape, and adapting to fluctuating energy prices and geopolitical instability. Opportunities exist in developing and deploying CCUS technologies, investing in research and development of cleaner hydrocarbon utilization methods, and repurposing existing infrastructure for other energy sources or industrial applications.

The development of blue hydrogen (produced from natural gas with carbon capture) offers a potential pathway to integrate hydrocarbons into a low-carbon energy system.

Hypothetical Energy Landscape in 2050

In a hypothetical scenario in 2050, renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, and hydropower dominate the global energy mix, accounting for over 60% of electricity generation. Hydrocarbon reserves continue to play a role, but primarily in sectors difficult to decarbonize immediately, such as heavy industry, aviation, and long-haul transportation. Natural gas, due to its relative cleanliness compared to coal, might maintain a significant, albeit reduced, share in power generation, particularly in regions with limited renewable energy resources or robust grid infrastructure.

Hydrocarbon reserves are a crucial global resource, impacting everything from energy production to geopolitical stability. Thinking about the scale of infrastructure needed to manage these reserves, it’s interesting to consider how technology can help with design; for example, check out these top rated AI home design websites with easy user interfaces to see how AI is streamlining complex projects.

Ultimately, efficient design, whether for homes or energy facilities, is vital for responsible hydrocarbon reserve management.

CCUS technologies are widely deployed, mitigating the environmental impact of remaining hydrocarbon use. This scenario reflects a balanced approach where renewable energy sources are prioritized, but hydrocarbons continue to serve as a transition fuel and play a niche role in specific sectors until viable alternatives become available at scale. This transition, however, is not uniform globally, with developing economies potentially exhibiting a higher reliance on hydrocarbons for a longer period.

The success of this transition will hinge on effective policy frameworks, technological advancements, and international cooperation.

Final Thoughts: Hydrocarbon Reserves

In conclusion, hydrocarbon reserves remain a pivotal element in the global energy mix, despite the growing push towards renewable energy sources. Their geological formation, exploration, extraction, and geopolitical significance are intrinsically linked, creating a complex web of economic, environmental, and political considerations. While the future undoubtedly holds a shift towards more sustainable energy options, understanding the current state and future trajectory of hydrocarbon reserves is crucial for informed decision-making and responsible resource management.

The challenges and opportunities presented by these reserves demand a nuanced approach, balancing energy security with environmental stewardship to ensure a stable and sustainable energy future for all.

FAQ Corner

What are the main environmental concerns associated with oil spills?

Oil spills cause significant harm to marine and coastal ecosystems, impacting wildlife through toxicity and habitat destruction. Cleanup efforts are often complex and costly, with long-term ecological consequences.

How long does it take to replenish hydrocarbon reserves?

The formation of hydrocarbon reserves takes millions of years, making them essentially non-renewable on a human timescale. Current extraction rates far exceed natural replenishment.

What are the economic benefits of owning hydrocarbon reserves for a country?

Countries with significant hydrocarbon reserves can benefit from substantial revenue through exports, creating jobs and boosting national income. However, this can also lead to economic volatility depending on global market prices.

What are some alternative energy sources that can replace hydrocarbons?

Several alternatives exist, including solar, wind, hydro, geothermal, and nuclear energy, along with biofuels. The transition to these sources requires significant investment and infrastructure development.

What is the difference between proven and probable reserves?

Proven reserves have a high degree of certainty regarding their existence and recoverability, while probable reserves have a lower certainty but are still considered commercially viable.