Directional Drilling is far more than just digging a hole; it’s a sophisticated engineering feat that allows us to reach otherwise inaccessible resources and create underground infrastructure with precision. From its humble beginnings, this technology has evolved dramatically, employing advanced tools and techniques to navigate complex subsurface formations. This guide will explore the principles, methods, applications, and future of this crucial field.

We’ll delve into the various directional drilling techniques, comparing and contrasting their strengths and weaknesses, examining the specialized equipment involved, and outlining the meticulous planning required for successful projects. We’ll also address the inherent challenges and risks, highlighting safety protocols and mitigation strategies. Finally, we’ll look at how directional drilling is revolutionizing industries ranging from oil and gas extraction to geothermal energy development and beyond.

Introduction to Directional Drilling

Directional drilling is a specialized drilling technique used to bore wells that deviate from a vertical path. This allows access to subsurface targets that are not directly beneath the drilling rig, opening up a wide range of possibilities in various industries. It’s a sophisticated process involving precise control and advanced technology to navigate underground formations safely and efficiently.Directional drilling fundamentally relies on the controlled bending of the drill string, the long column of pipes used to reach the target.

This bending is achieved using specialized downhole tools, such as bent subs and steerable motors, that allow the drill bit to change direction. Sensors and sophisticated guidance systems continuously monitor the wellbore’s trajectory, enabling operators to adjust the drilling path in real-time to reach the desired target with high accuracy. The process involves careful planning and modeling of the subsurface formations to predict and mitigate potential challenges.

Historical Overview of Directional Drilling Technology Advancements

Early directional drilling efforts, dating back to the early 20th century, involved rudimentary techniques with limited accuracy. The use of whipstocks, essentially wedge-shaped devices inserted into the wellbore to initiate a directional deviation, represented a significant early step. However, these methods were imprecise and often resulted in unpredictable well paths. Subsequent advancements included the development of mud motors, which provided a more controlled and powerful way to steer the drill bit.

The introduction of measurement-while-drilling (MWD) technology, which provides real-time data on the wellbore’s trajectory, revolutionized the industry. More recently, the integration of advanced technologies like rotary steerable systems (RSS) and sophisticated software for wellbore planning has enabled extremely precise and complex directional drilling operations, even in challenging geological formations.

Applications of Directional Drilling Across Industries

Directional drilling finds widespread application across multiple sectors. In the oil and gas industry, it’s crucial for accessing multiple reservoirs from a single surface location, minimizing environmental impact and maximizing resource extraction. This includes techniques like horizontal drilling, which significantly increases the contact area with the reservoir, boosting production. In the geothermal energy sector, directional drilling facilitates the creation of efficient geothermal wells for electricity generation and district heating.

The water well industry uses directional drilling to access groundwater resources in challenging geological settings, providing access to water in areas where traditional vertical wells might fail. Furthermore, directional drilling plays a significant role in environmental remediation, allowing for the precise placement of monitoring wells and the targeted injection of remediation fluids. The mining industry also utilizes directional drilling for exploration and resource extraction, providing access to mineral deposits that are difficult to reach with conventional methods.

Finally, directional drilling is used in the construction industry for projects like microtunneling, enabling the installation of underground utilities without extensive surface disruption.

Types of Directional Drilling Techniques

Directional drilling encompasses a range of techniques employed to deviate a wellbore from its initial vertical trajectory. The choice of technique depends on factors such as the target formation’s geometry, the well’s overall design, and the specific geological challenges encountered. Different methods offer unique advantages and disadvantages, influencing project cost, time, and overall efficiency.

Several key directional drilling methods exist, each with its own applications and limitations. Understanding these differences is crucial for successful well planning and execution.

Slant Drilling

Slant drilling involves deviating the wellbore at a relatively shallow angle from the vertical. This technique is often used for accessing reservoirs located at a slight offset from the wellhead location, or for situations where a shallower angle is sufficient to reach the target. It’s typically simpler and less expensive than more complex directional drilling methods, making it suitable for straightforward applications.

Directional drilling, crucial in accessing hard-to-reach resources, often relies on precise pre-planning. This planning is significantly enhanced by using sophisticated visualizations, and check out these AI tools for creating realistic 3D models of home designs online for inspiration; the principles of accurate spatial representation are similar. Ultimately, the success of directional drilling hinges on the quality of its initial design and modeling.

However, the limited reach of slant drilling restricts its applicability to targets relatively close to the surface location. The shallower angle also means less subsurface area is accessed compared to horizontal drilling.

Horizontal Drilling

Horizontal drilling, as the name suggests, involves drilling a wellbore that is primarily horizontal. This technique is extensively used to access extended-reach reservoirs, maximizing contact with the producing formation and improving production efficiency. Horizontal wells are particularly beneficial in low-permeability formations where increased surface area contact significantly boosts hydrocarbon recovery. However, horizontal drilling requires sophisticated directional drilling equipment and expertise, leading to higher costs and increased complexity compared to slant drilling.

The extended reach also introduces challenges in wellbore stability and steering accuracy. A successful horizontal well in a shale gas play, for instance, might extend several kilometers from the surface location.

Multilateral Drilling

Multilateral drilling is a more advanced technique that creates multiple branches from a single wellbore. These branches can extend in various directions, allowing access to multiple reservoir zones or sections from a single wellhead. This significantly reduces the surface footprint compared to drilling multiple individual wells, resulting in cost savings and environmental benefits. Multilateral wells are particularly valuable in complex reservoir structures where multiple pay zones are present.

The complexity of multilateral drilling, however, increases the risk of wellbore instability and necessitates advanced drilling technologies and experienced personnel, leading to higher upfront costs. A good example is a multilateral well targeting multiple sand layers within a single reservoir formation.

| Feature | Slant Drilling | Horizontal Drilling | Multilateral Drilling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angle of Deviation | Relatively shallow (e.g., < 45 degrees) | Primarily horizontal (near 90 degrees) | Variable, depending on branch design |

| Reach | Limited | Extended | Extended, with multiple branches |

| Cost | Relatively low | High | Very High |

| Complexity | Low | High | Very High |

Equipment and Tools Used in Directional Drilling

Directional drilling relies on sophisticated equipment and specialized tools to precisely guide the drill bit along a predetermined path. The success of a directional drilling project hinges on the efficient operation and proper maintenance of these components, ensuring accurate trajectory control and data acquisition throughout the drilling process.Directional drilling rigs are complex machines incorporating various systems working in concert.

Directional drilling, a crucial technique in oil and gas extraction, requires precise calculations and planning. Similarly, designing a home needs careful consideration, and choosing the right tools is key. That’s why comparing different AI-powered home design platforms online, like those reviewed at comparing different AI powered home design platforms online , can be incredibly helpful. Just as directional drilling uses sophisticated technology, these platforms leverage AI to streamline the design process, resulting in efficient and innovative home plans.

The primary components include the drilling rig itself (providing power and hoisting capabilities), a top drive system (allowing precise control of rotational speed and torque), a mud system (circulating drilling fluid), and a sophisticated navigation and control system. These systems work together to guide the drill bit, manage drilling fluids, and monitor the borehole’s progress.

Directional Drilling Rig Components

A directional drilling rig comprises several key components working in unison. The top drive provides precise control over the drill string’s rotation, allowing for adjustments in torque and speed crucial for navigating complex formations. The mud pumps circulate drilling fluid, which cleans the hole, lubricates the drill bit, and carries cuttings to the surface. The drawworks system manages the hoisting and lowering of the drill string, while the rotary table (in some rigs) provides an alternative method of drill string rotation.

Sophisticated sensors and control systems monitor various parameters like weight on bit, torque, and drilling fluid properties, providing real-time feedback to the drilling crew. The entire system is often mounted on a mobile platform, allowing for relocation to different drilling sites.

Specialized Tools in Directional Drilling

Several specialized tools are integral to successful directional drilling. Mud motors are downhole power units that provide rotational force to the drill bit independent of the surface rotary system. This allows for directional adjustments and drilling in challenging conditions where conventional rotary drilling might be ineffective. Steerable motors, a type of mud motor, offer further directional control. They allow the drill string to be bent or steered by changing the orientation of the motor’s internal components, enabling precise adjustments to the wellbore trajectory.

Measurement-while-drilling (MWD) tools are essential for real-time monitoring of the borehole’s position, inclination, and azimuth. These tools transmit data wirelessly to the surface, allowing the drilling crew to make immediate corrections to maintain the desired trajectory. MWD tools often incorporate accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers to provide accurate positional data.

Drilling Fluids in Directional Drilling

Drilling fluids, also known as mud, play a crucial role in directional drilling. The properties of the drilling fluid are carefully selected and adjusted to optimize the drilling process and ensure wellbore stability. Different types of drilling fluids serve various purposes.

- Water-based muds: These are cost-effective and environmentally friendly, suitable for many formations. However, their effectiveness can be limited in certain geological conditions.

- Oil-based muds: These offer better lubricity and shale inhibition, ideal for challenging formations prone to swelling or instability. However, they are more expensive and present environmental concerns.

- Synthetic-based muds: These combine the benefits of oil-based muds with reduced environmental impact. They provide good lubricity and shale inhibition while minimizing environmental concerns.

- Polymer muds: These are designed for specific applications, such as drilling in environmentally sensitive areas or high-temperature, high-pressure wells. They can be tailored to provide specific properties.

The choice of drilling fluid depends on several factors, including the formation’s properties, environmental regulations, and economic considerations. Careful selection and management of drilling fluids are critical for successful directional drilling.

Planning and Design of Directional Wells

Designing a directional well involves carefully plotting its path underground to reach a specific target, often far from the surface location. This process requires sophisticated software, geological data, and a deep understanding of drilling mechanics to ensure the well reaches its objective safely and efficiently while minimizing risks and maximizing production. The trajectory is not simply a straight line; it’s a carefully calculated curve, often with multiple bends and changes in direction.Precise wellbore positioning is critical for successful directional drilling.

Directional drilling is a crucial technique used to reach hard-to-access oil and gas reserves. This specialized drilling method is often employed on Oil Rig platforms, allowing for efficient extraction from unconventional locations. The precision of directional drilling ensures that wells are accurately placed, maximizing resource recovery and minimizing environmental impact.

Inaccurate placement can lead to missed targets, reduced hydrocarbon recovery, and potential damage to other wells or subsurface structures. Surveying techniques, employing various measurement-while-drilling (MWD) and logging-while-drilling (LWD) tools, continuously monitor the well’s position and orientation, allowing for real-time adjustments to maintain the planned trajectory. This constant monitoring and correction ensure the well remains on course, maximizing the chances of hitting the target.

Directional Well Trajectory Design

The design of a directional well trajectory begins with identifying the surface location and the target subsurface location. This involves analyzing geological data, including seismic surveys and well logs from nearby wells, to create a 3D model of the subsurface. Software programs then use this data to plan the optimal path, considering factors such as formation strength, potential hazards, and the desired wellbore inclination and azimuth.

The resulting trajectory is typically represented as a series of points, each with its own coordinates and inclination/azimuth angles. These points define the planned path of the drill bit. Different trajectory types, such as build and hold, S-shaped, or J-shaped, are selected based on the specific geological conditions and target location. For instance, an S-shaped trajectory might be used to navigate around an obstacle, while a J-shaped trajectory could be ideal for reaching a target located at a significant distance from the surface location.

Directional drilling allows for precise well placement, navigating underground formations to reach specific targets. This technique is often crucial for accessing resources in challenging geological areas, especially when combined with processes like Fracking (Hydraulic Fracturing) , which itself relies on accurately positioned wells to maximize extraction. Ultimately, the effectiveness of fracking hinges on the precision offered by directional drilling technology.

The Importance of Surveying and Wellbore Positioning

Accurate surveying and wellbore positioning are paramount throughout the entire drilling process. Real-time data acquired through MWD and LWD tools provide continuous updates on the well’s position, inclination, and azimuth. This information is crucial for making necessary adjustments to the drilling parameters (e.g., weight on bit, rotary speed, and mud flow rate) to maintain the planned trajectory. Discrepancies between the planned and actual wellbore path are identified and corrected using steering tools and advanced drilling techniques.

Without precise surveying and positioning, the well may deviate significantly from its planned path, leading to various complications, including the failure to reach the target, increased drilling costs, and potential safety hazards. Regular surveys also help identify potential problems, such as wellbore instability or unexpected geological formations, allowing for timely intervention and mitigation.

Step-by-Step Guide for Planning a Directional Drilling Operation

Planning a directional drilling operation requires a systematic approach, beginning well before the drilling rig arrives on location.

- Preliminary Site Survey and Data Acquisition: This involves a thorough review of existing geological data, including seismic surveys, well logs, and core samples from nearby wells. The purpose is to understand the subsurface geology and identify potential hazards or challenges. This stage also includes environmental impact assessments and logistical planning for the drilling site.

- Trajectory Design and Optimization: Using specialized software, a detailed well trajectory is designed. This includes determining the surface location, target location, and the optimal path connecting the two. The design considers various factors, such as formation strength, anticipated pressure gradients, and potential obstacles.

- Wellbore Stability Analysis: Analyzing the expected stresses on the wellbore during drilling helps prevent wellbore collapse or other instability issues. This analysis informs decisions on drilling mud type and weight, casing design, and drilling parameters.

- Equipment and Tool Selection: Selecting the appropriate drilling equipment, including the drill string, mud pumps, and downhole tools (MWD/LWD, steering tools), is essential for efficient and safe drilling. The selection depends on the well’s trajectory complexity and the expected geological conditions.

- Drilling Program Development: A detailed drilling program is created outlining all aspects of the operation, including the drilling plan, safety procedures, and contingency plans for potential problems. This program also defines the roles and responsibilities of the drilling crew.

- Pre-Drilling Considerations: This includes securing all necessary permits and approvals, finalizing logistics, and ensuring that all necessary equipment and personnel are in place and ready before drilling commences. Rig mobilization, mud system setup, and wellhead installation are key activities during this stage.

Challenges and Risks in Directional Drilling

Directional drilling, while offering significant advantages in accessing hard-to-reach reserves, presents a unique set of challenges and risks that demand careful planning, advanced technology, and rigorous safety protocols. These challenges stem from the complex nature of manipulating the drill string and bit through tortuous well paths, often in challenging geological formations. Failure to adequately address these risks can lead to costly delays, environmental damage, and even serious accidents.Directional drilling operations inherently involve a higher degree of complexity compared to vertical drilling, increasing the probability of encountering unforeseen issues.

These issues can range from minor equipment malfunctions to major wellbore instability events, significantly impacting project timelines and budgets. Effective risk mitigation strategies are crucial for successful directional drilling projects.

Wellbore Instability

Wellbore instability is a major concern in directional drilling, particularly when traversing through formations with varying strengths and stresses. Changes in pressure, temperature, and the inherent weaknesses of the rock formations can lead to wellbore collapse, stuck pipe, or other complications. These issues can cause significant non-productive time (NPT) and potentially necessitate costly remedial actions such as sidetracking (drilling a new wellbore from a point offset from the original).

Mitigation strategies include advanced geomechanical modeling to predict potential instability zones, optimizing mud weight and properties to manage pore pressure, and employing specialized drilling fluids and techniques to stabilize the wellbore. For example, using high-viscosity muds can provide better support to the wellbore walls in weak formations, reducing the risk of collapse.

Hole Cleaning

Effective hole cleaning is crucial in directional drilling to prevent cuttings accumulation, which can lead to pipe sticking, inaccurate wellbore trajectory, and ultimately, well control issues. The complex geometry of directional wells makes it challenging to efficiently remove cuttings from the bottom of the hole. Factors such as inclination, azimuth, and the presence of tortuous sections can hinder the upward flow of cuttings.

Mitigation strategies involve optimizing drilling parameters such as rotational speed and weight on bit, employing specialized drilling fluids with enhanced carrying capacity, and utilizing advanced hole cleaning tools and technologies. For instance, using a high-velocity jetting system can improve cuttings removal efficiency in challenging wellbore geometries.

Equipment Malfunctions

Directional drilling relies on a complex interplay of sophisticated equipment, including the mud pumps, top drives, downhole motors, and measurement-while-drilling (MWD) systems. Malfunctions in any of these components can significantly disrupt operations, potentially resulting in costly repairs, delays, and even well abandonment. Regular equipment maintenance, thorough pre-job inspections, and redundancy systems are crucial for mitigating equipment-related risks. For instance, having backup pumps and power sources can minimize downtime in the event of a primary system failure.

Furthermore, advanced diagnostic tools and real-time monitoring systems can help identify potential problems before they escalate into major incidents.

Safety Procedures and Regulations

Safety is paramount in directional drilling operations, given the inherent risks associated with high-pressure environments, heavy machinery, and the potential for well control issues. Stringent safety procedures and regulations, such as those mandated by organizations like the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the American Petroleum Institute (API), must be strictly adhered to. These regulations cover aspects such as personal protective equipment (PPE), emergency response planning, well control procedures, and environmental protection.

Regular safety training for personnel, thorough risk assessments, and the implementation of robust safety management systems are essential to minimize the risk of accidents and injuries. For example, regular drills and simulations of emergency situations ensure that personnel are well-prepared to respond effectively in case of a well control incident.

Applications of Directional Drilling in Different Industries

Directional drilling’s ability to deviate from a vertical path offers significant advantages across various sectors, allowing access to resources and infrastructure development in previously unreachable locations. This adaptability makes it a crucial technology for efficient and cost-effective operations.Directional drilling techniques are employed to overcome geographical limitations and optimize resource extraction. The precision and control offered by these methods minimize environmental impact and maximize the economic viability of projects.

This section explores the diverse applications of directional drilling across several key industries.

Directional Drilling in the Oil and Gas Industry

The oil and gas industry is the most prominent user of directional drilling. Extended reach drilling allows access to reservoirs far from the drilling location, minimizing surface infrastructure and environmental disruption. This is particularly beneficial in offshore operations and environmentally sensitive areas. Horizontal drilling, a specialized form of directional drilling, is crucial for shale gas extraction. By creating long horizontal wells within the shale formation, it maximizes contact with the gas-bearing rock, significantly increasing production.

For example, the Bakken formation in North Dakota and Montana relies heavily on horizontal drilling to unlock its vast shale gas reserves. The increased surface area contact with the reservoir improves the efficiency of hydraulic fracturing, a process used to release the trapped gas.

Directional drilling techniques are crucial for accessing hard-to-reach resources, but efficient planning is key. This is where online AI home design software that considers sustainability can surprisingly help; optimizing building layouts for resource efficiency mirrors the precision needed in directional drilling path optimization. Ultimately, both fields demand careful planning and innovative solutions for optimal outcomes.

Directional Drilling in Geothermal Energy

Directional drilling plays a vital role in geothermal energy production. Geothermal reservoirs are often located at significant depths and can be difficult to access using conventional vertical drilling. Directional drilling enables the creation of wells that reach optimal geothermal zones, maximizing energy extraction. Moreover, the ability to steer the drill bit allows for the precise placement of wells to avoid geological obstacles and optimize energy output.

For instance, in Iceland, directional drilling is used to tap into high-temperature geothermal resources for electricity generation and district heating systems. The ability to precisely target productive geothermal zones minimizes drilling time and maximizes the return on investment.

Directional Drilling in Mining

In the mining industry, directional drilling offers several advantages. It allows for the creation of access tunnels and exploration boreholes in challenging geological environments, reducing the need for extensive surface excavations. This is especially beneficial in mountainous regions or areas with unstable ground conditions. Directional drilling can also be used to access mineral deposits that are otherwise difficult or impossible to reach using conventional mining techniques.

For example, directional drilling is employed in underground coal mining to create ventilation shafts and access tunnels, improving safety and efficiency. The precise placement of boreholes helps minimize environmental impact and reduce the risk of ground instability.

Directional Drilling in Underground Infrastructure Development

Directional drilling is increasingly used in the development of underground infrastructure, including pipelines, utility lines, and cable installations. This method avoids surface disruption and minimizes environmental impact, making it ideal for urban areas and environmentally sensitive regions. The ability to steer the drill bit allows for the precise placement of pipelines and cables, reducing the risk of damage and ensuring the longevity of the infrastructure.

For example, directional drilling is used to install pipelines under rivers and roads, minimizing the need for extensive excavation and traffic disruption. The reduced environmental impact and minimized disruption make directional drilling a cost-effective and environmentally friendly solution for underground infrastructure development.

Future Trends and Innovations in Directional Drilling

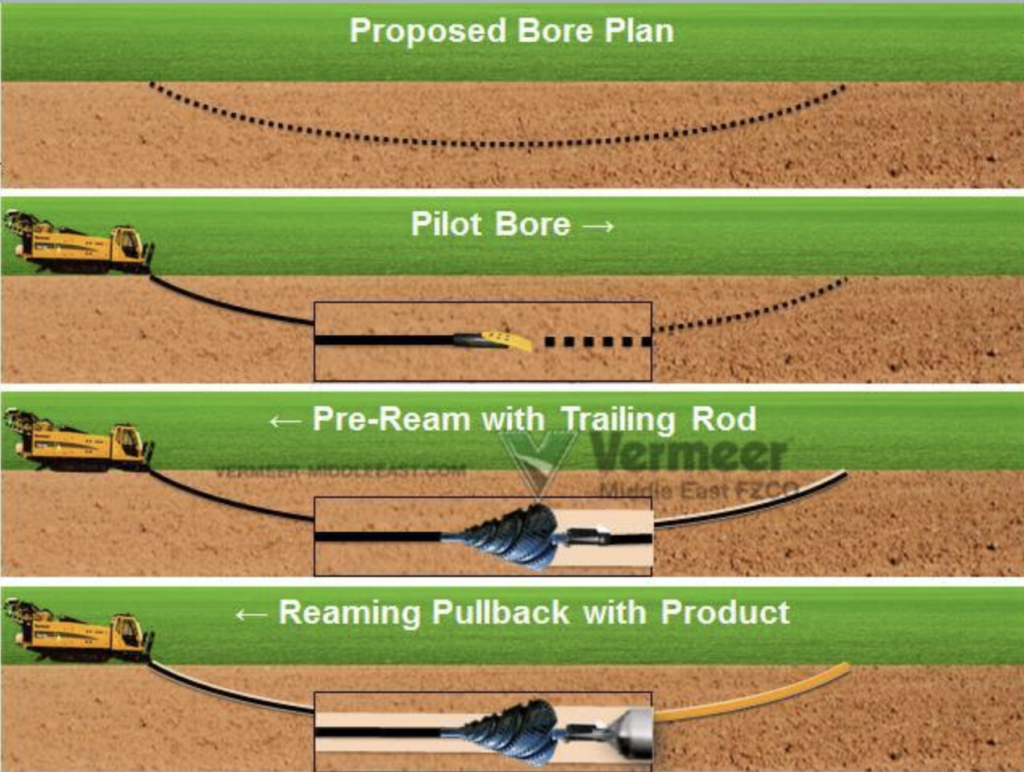

Source: vermeer-middleeast.com

Directional drilling is a constantly evolving field, driven by the need for greater efficiency, precision, and access to increasingly challenging subsurface resources. New technologies and innovative approaches are continuously being developed to address the limitations of traditional methods and unlock new possibilities in reservoir access and well placement.The future of directional drilling hinges on enhanced automation, sophisticated data analysis, and the integration of advanced materials and techniques.

Directional drilling is a crucial technique used to reach hard-to-access reservoirs, often requiring precise maneuvering underground. This is especially relevant in onshore operations, where the terrain can present unique challenges; for more information on the specifics of this type of operation, check out this page on Onshore Drilling. Understanding the complexities of onshore drilling helps refine directional drilling strategies and maximize well placement efficiency.

These advancements are not only improving the speed and accuracy of drilling operations but also minimizing environmental impact and maximizing resource recovery.

Advanced Drilling Automation

Automation is revolutionizing directional drilling by reducing human error, increasing efficiency, and enabling operations in more challenging environments. Systems employing artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are being developed to optimize drilling parameters in real-time, predicting potential issues, and automatically adjusting drilling strategies to maintain optimal performance. For example, automated mud pumps can adjust pressure based on real-time sensor data, preventing issues like wellbore instability.

Furthermore, robotic systems are being explored for tasks like tool handling and wellhead maintenance, enhancing safety and reducing the need for human intervention in hazardous conditions.

Real-Time Data Analytics and Predictive Modeling

The vast amount of data generated during directional drilling operations—from downhole sensors, surface measurements, and geological models—presents an opportunity for significant improvement through sophisticated data analytics. Real-time analysis of this data allows for immediate identification of anomalies and potential problems, enabling proactive adjustments to the drilling plan and preventing costly downtime. Predictive modeling, utilizing machine learning algorithms, can forecast potential drilling challenges such as formation instability or unexpected geological formations, enabling drillers to make informed decisions and optimize drilling parameters accordingly.

For instance, by analyzing data on drilling rate, torque, and weight on bit, algorithms can predict the likelihood of a bit failure and suggest preventative measures.

Directional drilling is a crucial technique for accessing hard-to-reach areas within a geological formation. This precision is especially important when targeting specific zones within a Reservoir , maximizing oil and gas extraction. By carefully controlling the wellbore trajectory, directional drilling ensures efficient production from the reservoir, ultimately optimizing the overall operation.

Potential Future Applications of Directional Drilling

The continuous advancements in directional drilling technology are expanding its applications beyond traditional oil and gas extraction. One promising area is geothermal energy exploration, where directional drilling can access deep geothermal reservoirs more efficiently and cost-effectively. Similarly, it’s playing a crucial role in carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects, allowing for the precise placement of injection wells for sequestering CO2 deep underground.

Directional drilling, a crucial technique in oil and gas extraction, requires precise planning. This precision extends even to the design of support facilities, and for optimizing kitchen spaces in those facilities, you might find the best AI home design software for creating custom kitchen designs helpful. Ultimately, efficient design, whether for a drilling rig or a kitchen, saves time and resources, mirroring the goals of directional drilling itself.

Moreover, directional drilling is becoming increasingly important in various infrastructure projects, such as installing underground pipelines and utilities with minimal surface disruption.

Potential Research Areas in Directional Drilling

The continued advancement of directional drilling relies on focused research and development efforts. Key areas for future research include:

- Development of more robust and durable drilling tools capable of withstanding higher temperatures and pressures, and operating in more challenging geological formations.

- Advanced sensor technologies providing higher-resolution data on downhole conditions, enabling more precise real-time monitoring and control.

- Improved drilling fluids and completion techniques to minimize environmental impact and enhance wellbore stability.

- Development of AI and ML algorithms for automated well planning and real-time drilling optimization.

- Exploration of new materials and manufacturing processes to create lighter, stronger, and more cost-effective drilling equipment.

- Research into novel drilling techniques, such as laser drilling or plasma drilling, to improve efficiency and reduce environmental impact.

Case Studies

This section details two successful directional drilling projects, illustrating the complexities involved and the positive outcomes achieved. The case studies highlight the careful planning, advanced technology, and skilled execution required for successful directional drilling operations, emphasizing the challenges overcome and the resulting benefits. Each example includes a description of the well trajectory, relevant drilling parameters, and the ultimate project results.

Successful Directional Drilling Project: Offshore Oil Well in the Gulf of Mexico

This project involved drilling an extended-reach well in a challenging offshore environment in the Gulf of Mexico. The target reservoir was located approximately 10 kilometers from the drilling platform, requiring a highly complex well trajectory to navigate through various geological formations and avoid potential hazards. The well path began with a vertical section of approximately 500 meters, followed by a build section with an inclination rate of 2 degrees per 30 meters to reach a target inclination of 60 degrees.

This build section was approximately 3 kilometers long. The well then transitioned to a hold section, maintaining the 60-degree inclination for another 3 kilometers, before a final short build section to reach the target reservoir. The total measured depth (MD) was approximately 10 kilometers, while the true vertical depth (TVD) was around 8 kilometers.The drilling parameters included a rotary steerable system (RSS) for precise directional control, advanced mud monitoring to manage formation pressure, and real-time data acquisition to optimize drilling parameters.

The major challenge was maintaining wellbore stability in the highly pressured and complex geological formations encountered. This was successfully mitigated through the use of specialized drilling fluids and advanced wellbore stability models. The project resulted in the successful completion of the well, achieving the planned trajectory and delivering significant hydrocarbon production. The well path can be visualized as an initially vertical line transitioning into a gradually curving line, steepening to a 60-degree angle, maintaining that angle for a considerable distance, and then slightly increasing the angle again before reaching the target reservoir deep below the seafloor.

The entire path resembles a long, gently curving arc that deepens significantly under the seabed.

Successful Directional Drilling Project: Geothermal Well in Iceland

This project focused on drilling a highly deviated geothermal well in Iceland to access a deep geothermal reservoir. The target reservoir was located at a significant depth and offset from the surface location, necessitating a highly deviated well path. The well trajectory started with a vertical section of approximately 500 meters, followed by a build section to reach a maximum inclination of 80 degrees over a distance of 2 kilometers.

A long hold section maintained this steep inclination for approximately 3 kilometers before a short, controlled build section to intersect the target reservoir. The total measured depth was around 5 kilometers, with a true vertical depth of approximately 1 kilometer.The primary challenges included maintaining directional control in the highly fractured and heterogeneous geothermal formations, and managing high temperatures and pressures.

This required the use of a high-temperature-high-pressure (HTHP) drilling system, advanced drilling fluids, and real-time monitoring of wellbore conditions. The use of a downhole motor assisted in navigating the challenging formations. The successful completion of this well provided access to a significant geothermal resource, providing a sustainable energy source for the region. The well path is best described as a near-vertical initial section transitioning rapidly to a very steep angle, essentially a near-horizontal path extending for a significant distance, then curving only slightly to intersect the reservoir at a considerable depth.

The overall shape is a short, nearly vertical line followed by a long, almost horizontal line with a slight upward curve at the end.

Final Thoughts

Directional drilling represents a remarkable achievement in engineering and technology, constantly pushing the boundaries of what’s possible beneath the Earth’s surface. Its applications are diverse and ever-expanding, promising innovative solutions to resource extraction, infrastructure development, and environmental challenges. As technology continues to advance, we can expect even greater precision, efficiency, and safety in directional drilling operations, unlocking new possibilities for exploration and development across a wide range of industries.

Questions and Answers

What are the environmental concerns associated with directional drilling?

Environmental concerns can include potential groundwater contamination from drilling fluids, habitat disruption, and greenhouse gas emissions from energy consumption. Mitigation strategies focus on using environmentally friendly fluids, minimizing surface disturbance, and optimizing energy efficiency.

How is the accuracy of directional drilling ensured?

Accuracy is maintained through sophisticated surveying techniques, including measurement-while-drilling (MWD) tools that provide real-time data on wellbore trajectory. This data allows for constant adjustments to the drilling path, ensuring the well reaches its target precisely.

What are the typical costs involved in a directional drilling project?

Costs vary greatly depending on factors such as well depth, complexity of the subsurface formation, required equipment, and location. It’s a significant investment, but the potential rewards often outweigh the expenses, especially in resource extraction.

What are the career opportunities in directional drilling?

Numerous opportunities exist for engineers, geologists, technicians, and other skilled professionals. Roles range from drilling engineers and project managers to specialized technicians operating and maintaining drilling equipment.