Exploration Well: The thrill of discovery lies at the heart of the petroleum industry, and nowhere is this more evident than in the risky, yet potentially lucrative, world of exploration wells. These wells represent the initial foray into uncharted geological territory, a gamble that could unearth vast reserves or yield nothing but disappointment. From initial planning based on seismic surveys and geological models to the complex drilling operations and sophisticated formation evaluation techniques, the journey of an exploration well is a fascinating blend of science, technology, and high stakes.

This journey begins long before the drill bit touches the ground. Extensive research, including seismic surveys and geological analysis, helps pinpoint promising locations. The design phase involves meticulous planning, considering factors like wellbore trajectory, casing design, and drilling fluids. The actual drilling process itself is a complex operation, often involving advanced directional drilling techniques to navigate challenging geological formations.

Once the well is drilled, sophisticated logging tools and core samples are used to analyze the formations encountered. Finally, well testing helps determine the reservoir’s properties and its potential for production. All these steps are undertaken with careful consideration for environmental regulations and economic viability.

Definition and Purpose of Exploration Wells

Exploration wells are crucial in the petroleum industry, acting as the initial investigative step in identifying and assessing potential hydrocarbon reserves beneath the Earth’s surface. They are drilled in areas where the presence of oil and gas is suspected, but not yet confirmed. The primary purpose is to determine the presence, quantity, and quality of hydrocarbons within a specific geological formation.The main objectives of drilling an exploration well are threefold: to confirm the presence of hydrocarbons, to evaluate the reservoir’s characteristics (porosity, permeability, fluid saturation), and to obtain samples for laboratory analysis.

This information is vital for determining the commercial viability of a potential oil or gas field. Failure to achieve these objectives often leads to the well being plugged and abandoned, representing a significant financial investment loss.

Types of Exploration Wells

Exploration wells are categorized based on their location relative to known discoveries and the level of geological risk involved. Understanding these classifications helps assess the potential success and associated financial risk of each drilling operation.

- Wildcat Wells: These are drilled in completely unexplored areas, where there is little or no prior geological data to indicate the presence of hydrocarbons. They carry the highest risk but also the potential for significant rewards if successful. An example would be drilling in a remote, geologically complex area with limited prior seismic surveys.

- Step-Out Wells: These wells are drilled in areas adjacent to a known discovery, attempting to extend the boundaries of the existing field. They represent a lower risk than wildcats because of the proximity to a producing field, but success is still not guaranteed. A step-out well might target a geological structure similar to one found productive in a nearby field, but slightly offset.

Exploration wells are crucial for understanding subsurface geology, but designing the accompanying facilities can be complex. Luckily, streamlining the process is easier than ever thanks to affordable AI powered home design services available online , which can help optimize building layouts and resource allocation. This means exploration well projects can be planned more efficiently and cost-effectively, leading to faster completion times.

- Appraisal Wells: Once a discovery is made, appraisal wells are drilled to further define the size, shape, and productivity of the reservoir. They are used to obtain more detailed information about the reservoir’s properties and to plan future development activities. Appraisal wells often involve extensive testing and data acquisition to optimize production strategies. For example, after a successful wildcat well, several appraisal wells might be drilled to delineate the reservoir’s extent and determine the optimal well locations for production.

Comparison of Exploration and Production Wells

Exploration and production wells serve distinct purposes within the oil and gas industry. While both involve drilling into subsurface formations, their objectives and operational phases differ significantly.

| Feature | Exploration Well | Production Well |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Discover and assess hydrocarbon resources | Extract hydrocarbons |

| Risk Level | High | Low (generally) |

| Location | Unexplored or partially explored areas | Within known reservoirs |

| Testing | Limited testing, focused on reservoir characteristics | Extensive testing to optimize production |

| Completion | Often plugged and abandoned if unsuccessful | Completed for long-term hydrocarbon production |

Exploration Well Planning and Design

Exploration well planning and design is a critical phase in the oil and gas exploration process, directly impacting the success and efficiency of the operation. A well-planned exploration well minimizes risks, optimizes resource allocation, and maximizes the chances of discovering commercially viable hydrocarbon reserves. This involves integrating geological, geophysical, and engineering data to create a detailed plan for drilling and testing the well.

Geological and Geophysical Data Used in Exploration Well Planning

Geological and geophysical data provide the foundation for exploration well planning. Geological data, including surface geology maps, subsurface formations interpretations from seismic surveys, and well logs from nearby wells, help define the potential reservoir characteristics, such as rock type, porosity, permeability, and hydrocarbon saturation. Geophysical data, primarily from seismic surveys (2D and 3D), offer a three-dimensional image of the subsurface, revealing structural features like faults and folds, and stratigraphic variations that may indicate the presence of hydrocarbon traps.

These data are integrated to identify promising drilling locations and predict the subsurface conditions the well will encounter. For example, seismic data might show a structural closure (anticlinal trap) where hydrocarbons could accumulate, while well logs from offset wells might indicate the presence of similar reservoir rock types.

Steps Involved in Designing an Exploration Well Program

Designing an exploration well program is an iterative process involving several key steps. First, a location is selected based on the integrated interpretation of geological and geophysical data, aiming to maximize the probability of encountering hydrocarbons. Next, a wellbore trajectory is planned, considering factors such as subsurface formations, potential hazards (faults, high-pressure zones), and surface constraints. This is followed by casing design, where the size and strength of the steel casing are determined to withstand the expected pressure and temperature conditions at each depth interval.

The selection of drilling fluids is also crucial, as they must maintain wellbore stability, control pressure, and prevent formation damage. Finally, a detailed drilling plan is developed, including rig selection, drilling program, and safety procedures. This entire process often involves multiple revisions and refinements based on new data or changes in circumstances.

Key Parameters Considered During Well Design

| Parameter | Description | Considerations | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wellbore Trajectory | The planned path of the wellbore through the subsurface. | Geological structures, target depth, and surface constraints. | Vertical, deviated, or horizontal well. |

| Casing Design | The size, grade, and weight of steel casing used to support the wellbore and prevent collapse. | Formation pressure, temperature, and wellbore stability. | Multiple strings of casing with varying specifications. |

| Drilling Fluids | The fluid used to circulate cuttings out of the wellbore and control pressure. | Formation properties, pressure gradients, and environmental regulations. | Water-based mud, oil-based mud, or synthetic-based mud. |

| Drilling Program | Detailed plan outlining the drilling operations, including bit selection, rate of penetration, and mud weight. | Formation characteristics, drilling equipment, and safety regulations. | Specific drilling parameters for each formation encountered. |

Risk Assessment Process Associated with Exploration Well Planning

Risk assessment is a crucial aspect of exploration well planning. It involves identifying potential hazards and assessing their likelihood and consequences. Common risks include wellbore instability, formation pressure kicks, equipment failure, and environmental incidents. A thorough risk assessment uses qualitative and quantitative methods, such as Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA) and probabilistic risk assessment, to evaluate the probability and severity of each risk.

Mitigation strategies are then developed to reduce the likelihood or severity of these risks, potentially involving alternative well designs, specialized equipment, or enhanced safety procedures. For instance, a high-pressure zone identified in the risk assessment might lead to the selection of stronger casing or the use of specialized drilling fluids. Regular reviews and updates to the risk assessment are necessary throughout the well planning and execution phases to account for new information or changing conditions.

Drilling Operations and Technologies

Exploration well drilling is a complex undertaking, requiring specialized equipment and expertise to navigate diverse subsurface conditions. The choice of drilling techniques and technologies significantly impacts the efficiency, cost, and safety of the operation. Success hinges on careful planning, precise execution, and adaptability to unexpected geological challenges.

Drilling Techniques Employed in Exploration Wells

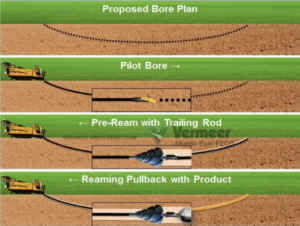

Several drilling techniques are employed depending on factors such as the target depth, geological formations, and the well’s trajectory. Rotary drilling, the most common method, uses a rotating drill bit to cut through the rock. This process involves circulating drilling mud to remove cuttings, stabilize the borehole, and control pressure. Other techniques include percussion drilling, suitable for softer formations, and directional drilling, used to reach targets that are not directly beneath the drilling location.

Specialized techniques like underbalanced drilling might be employed in certain sensitive formations to minimize formation damage.

Challenges Associated with Drilling in Different Geological Formations

Drilling presents unique challenges depending on the geological environment. Hard, abrasive formations like granite require robust drill bits and higher drilling rates. Conversely, soft formations may collapse easily, necessitating careful wellbore stabilization. High-pressure zones pose risks of blowouts, demanding precise pressure control. Unconsolidated formations may require specialized drilling fluids to prevent wellbore instability.

The presence of faults, fractures, and unexpected geological features can also significantly complicate the drilling process and necessitate adjustments to the drilling plan. For example, drilling through a shale formation might require specialized mud formulations to prevent swelling or fracturing of the shale, potentially causing wellbore instability. Similarly, drilling through a highly fractured limestone formation requires careful monitoring of pressure to prevent loss of circulation.

Step-by-Step Description of the Drilling Process for an Exploration Well

The drilling process typically begins with surface preparations, including the construction of a drilling pad and the assembly of the drilling rig. Next, a surface hole is drilled to a predetermined depth, followed by the setting of surface casing to protect freshwater aquifers and provide stability. Intermediate casing is then set at progressively deeper intervals, further protecting the wellbore and isolating different geological formations.

The process continues with drilling deeper sections and setting additional casing strings as needed, all while carefully monitoring pressure and collecting geological data. Once the target depth is reached, the well is logged using various tools to gather data about the subsurface formations. Finally, the well is completed, potentially including the installation of production equipment if hydrocarbons are encountered.

The exact sequence and details may vary depending on the specific project requirements and geological conditions.

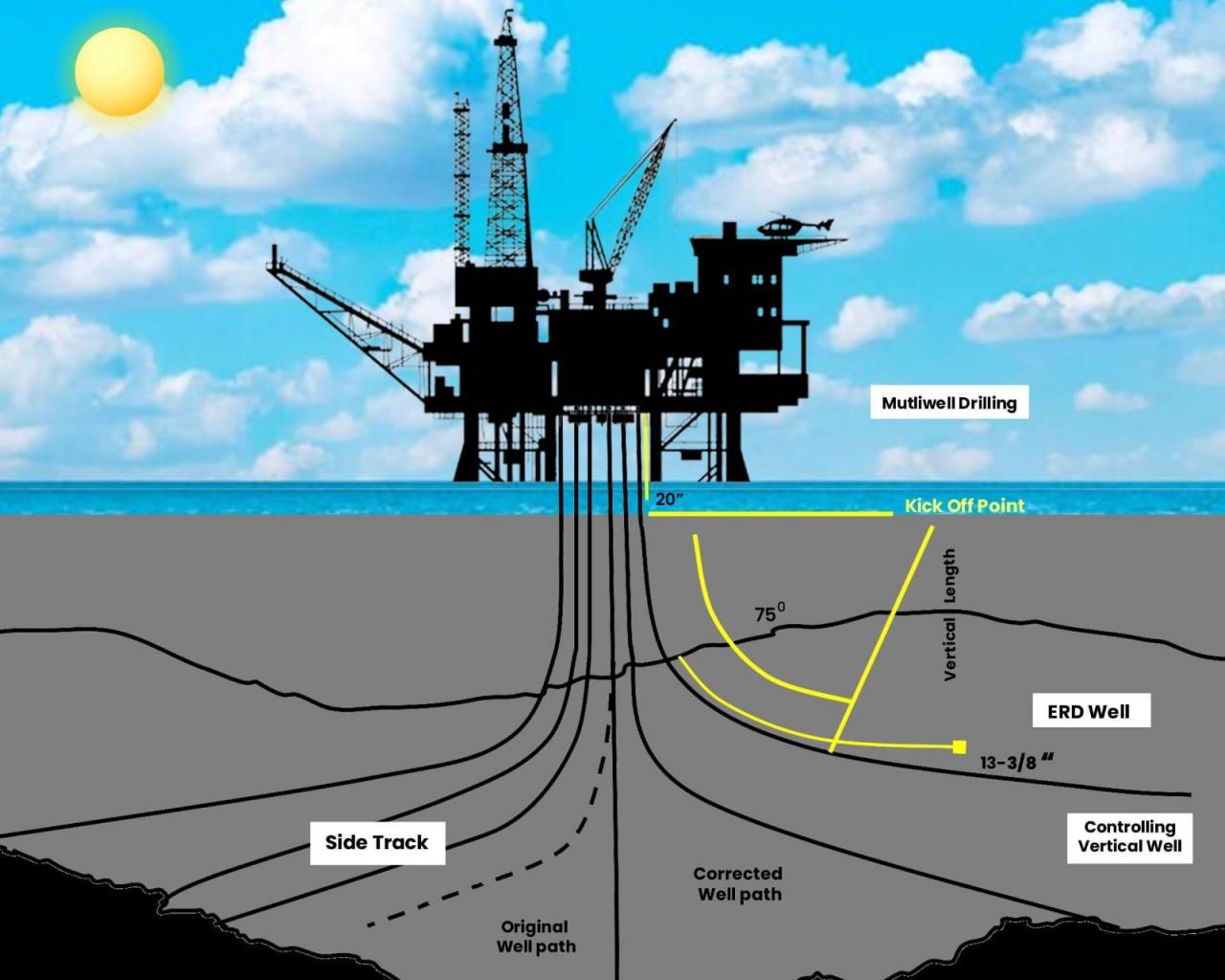

Comparison of Conventional and Directional Drilling Methods

Conventional drilling involves drilling a vertical well directly beneath the drilling location. This is a simpler and often less expensive method but limits access to targets offset from the surface location. Directional drilling, on the other hand, allows for the creation of deviated wells, reaching targets that are not vertically aligned with the surface location. This technique uses specialized downhole tools, such as bent subs and mud motors, to steer the drill bit along a pre-planned trajectory.

Directional drilling is more complex and expensive but offers greater flexibility in accessing subsurface targets, particularly in densely populated areas or environmentally sensitive locations. For instance, multiple wells can be drilled from a single surface location using directional drilling, minimizing the environmental footprint compared to drilling multiple vertical wells.

Exploration wells are crucial for understanding subsurface geology, much like planning a room’s layout is key to a comfortable home. When designing your ideal space, you might find helpful resources like online AI home design tools with furniture placement features to visualize the perfect arrangement. Similarly, detailed exploration well data helps visualize subsurface formations, guiding efficient resource extraction.

Formation Evaluation and Data Acquisition

Source: isu.pub

Formation evaluation is crucial in exploration wells; it provides the critical subsurface data needed to assess the commercial viability of a hydrocarbon discovery. This involves a suite of techniques aimed at characterizing the geological formations encountered during drilling, determining their fluid content, and ultimately estimating the reservoir’s potential. This data is gathered through a combination of wireline logging, core analysis, and mud logging.

Wireline Logging Tools and Techniques

Wireline logging employs various tools lowered into the wellbore on a cable to measure different physical properties of the formations. These tools transmit data to the surface in real-time, providing a continuous record of the formations’ characteristics. Common tools include gamma ray logs (measuring natural radioactivity), resistivity logs (measuring the ability of formations to conduct electricity), sonic logs (measuring the speed of sound through formations), density logs (measuring the bulk density of formations), and neutron logs (measuring the hydrogen index, indicative of porosity).

The combination of data from these different tools allows for a comprehensive understanding of the subsurface geology. For example, high gamma ray readings often indicate shale formations, while low resistivity readings suggest the presence of hydrocarbons.

Exploration wells are crucial for understanding subsurface geology, but planning the logistics can be complex. Designing efficient layouts for equipment and personnel is much easier with the help of top rated AI home design websites with easy user interfaces , which can create optimal space arrangements. These tools can then be adapted to streamline the exploration well site, ensuring safety and efficiency.

Interpreting Subsurface Geology from Logging Data

The data acquired from wireline logs is processed and interpreted using specialized software and geological expertise. Cross-plotting of different log responses allows geologists to identify lithology (rock type), porosity (the volume of pore space in the rock), water saturation (the percentage of pore space filled with water), and permeability (the ability of the rock to transmit fluids). These parameters are essential for determining the reservoir’s potential to produce hydrocarbons.

For instance, high porosity and low water saturation, coupled with good permeability, indicate a potentially productive reservoir. Advanced techniques like petrophysical modeling can be used to create detailed 3D representations of the reservoir, aiding in the planning of future development activities.

Core Sample Collection and Analysis

Core samples are cylindrical sections of rock retrieved from the wellbore during drilling. These samples provide direct visual observation of the formations and allow for detailed laboratory analysis. Core sampling is typically more expensive and less continuous than wireline logging but provides invaluable information for detailed petrophysical analysis. The core samples are analyzed for various properties, including porosity, permeability, lithology, and fluid content.

This detailed information helps to calibrate and validate the data obtained from wireline logs, leading to a more accurate reservoir characterization. Different types of coring techniques exist, including conventional wireline coring and rotary coring, each with its own advantages and disadvantages based on the formation’s characteristics and drilling conditions.

Types of Formation Evaluation Data

The following list summarizes the different types of formation evaluation data and their significance:

- Wireline Log Data: Provides continuous measurements of various physical properties throughout the wellbore. Crucial for initial reservoir characterization and identifying zones of interest.

- Core Analysis Data: Provides detailed laboratory measurements of rock properties from physical core samples. Used to calibrate wireline log data and obtain more precise reservoir parameters.

- Mud Logging Data: Provides real-time information on drilling parameters and cuttings analysis during drilling operations. Helps in identifying potential hydrocarbon zones and monitoring drilling progress.

- Fluid Sample Analysis: Analysis of fluids recovered from the formation, such as oil, gas, and water samples, to determine their properties (e.g., API gravity, gas composition). Essential for determining hydrocarbon type and quality.

- Pressure Data: Measurements of formation pressure at different depths, providing insights into reservoir pressure and fluid properties. Important for determining reservoir energy and productivity.

Well Testing and Analysis

Well testing is a crucial phase in exploration well operations, providing vital information about the reservoir’s properties and the well’s potential productivity. This data is essential for making informed decisions regarding further development and resource estimation. The process involves carefully controlled procedures to measure pressure, flow rates, and other parameters, ultimately helping to translate geological interpretations into economic viability.Well testing employs various methods to assess reservoir characteristics and well performance.

Exploration wells are crucial for discovering new resources, much like designing a home is a crucial step in creating a comfortable living space. Planning your dream home can be significantly easier with the help of AI powered home design software that integrates with smart home tech , allowing for precise control and efficient planning. Just as exploration wells require careful planning, so too does building your perfect smart home.

These methods are designed to acquire data under controlled conditions, allowing for accurate interpretation of reservoir properties. The choice of testing method depends on several factors, including the well’s depth, the reservoir’s pressure, and the anticipated fluid production.

Drill Stem Test (DST)

Drill stem tests are commonly used in exploration wells to evaluate the reservoir’s potential. A DST involves isolating a specific zone of interest within the wellbore using specialized tools, such as packers. After isolation, the pressure within the formation is measured, and then the formation is allowed to flow into the wellbore. Flow rates and pressure changes are carefully monitored to determine the reservoir’s pressure, permeability, and fluid properties.

The data acquired during a DST provides valuable insights into the reservoir’s potential productivity and the presence of hydrocarbons. For example, a DST might reveal a high-permeability sandstone with significant oil flow, indicating a potentially productive reservoir. Conversely, a low flow rate might suggest a tight reservoir or a lack of hydrocarbons.

Production Test

Production tests are conducted to assess the long-term productivity of a well. Unlike DSTs, which are relatively short-term tests, production tests can last for several days or even weeks. During a production test, the well is allowed to produce at a controlled rate, and the pressure and flow rate are continuously monitored. This data is used to determine the well’s productivity index (PI), which is a measure of the well’s ability to produce hydrocarbons.

A high PI indicates a highly productive well. For instance, a production test might show a consistent high flow rate of gas over a period of several days, indicating a potentially commercially viable gas reservoir. Conversely, a declining flow rate might signal reservoir depletion or formation damage.

Using Well Test Data to Assess Reservoir Properties

Well test data is used to determine key reservoir properties like permeability and porosity. Permeability, a measure of the rock’s ability to transmit fluids, is calculated from the pressure changes observed during a test. Porosity, representing the volume of pore space in the rock, is often estimated using correlations with other data, such as core analysis or seismic data.

By combining data from well tests with other geological and geophysical data, a more comprehensive understanding of the reservoir can be developed. For example, a high permeability value coupled with a high porosity value obtained from a well test suggests a highly productive reservoir with significant hydrocarbon storage capacity.

Hypothetical Well Test Procedure

This hypothetical procedure Artikels a DST for an exploration well targeting a suspected oil reservoir at approximately 3000 meters depth.

- Pre-test Preparations: This includes assembling the necessary equipment, such as drill stem testing tools (packers, flow control valves, pressure gauges), and reviewing the well’s geological information to identify the target zone.

- Wellbore Preparation: The well is cleaned and conditioned to ensure accurate measurements. This may involve running a wiper trip to remove cuttings.

- Setting Packers: Packers are run into the wellbore and set to isolate the target zone. This ensures that the fluid flow is only from the zone of interest.

- Pressure Build-up: The isolated zone is allowed to build up pressure to its initial reservoir pressure. This period allows the formation to reach equilibrium.

- Flow Period: The flow control valves are opened, and the formation fluids are allowed to flow into the wellbore. Flow rates and pressures are continuously monitored and recorded.

- Pressure Drawdown: After a period of flow, the valves are closed, and the pressure is allowed to recover. This pressure build-up data is analyzed to determine reservoir properties.

- Data Acquisition and Analysis: All pressure and flow rate data are recorded and analyzed to determine reservoir parameters such as permeability, porosity, and fluid properties.

- Post-Test Operations: The testing tools are retrieved from the wellbore, and the well is prepared for further operations.

Environmental Considerations and Regulations

Exploration well drilling, while crucial for discovering and developing energy resources, carries inherent environmental risks. These activities can impact air and water quality, soil and vegetation, and potentially even wildlife habitats. Understanding and mitigating these risks is paramount, guided by a robust regulatory framework and best practices.Environmental impacts associated with exploration well drilling are multifaceted. Air emissions from drilling rigs and support equipment can contribute to air pollution, releasing greenhouse gases and particulate matter.

Spills of drilling fluids, produced water, or hydrocarbons can contaminate soil and surface water, harming aquatic life and potentially affecting groundwater resources. Noise pollution from drilling operations can disrupt wildlife behavior and ecosystems. Land disturbance from well pads and access roads can lead to habitat fragmentation and erosion. Finally, the disposal of drilling waste requires careful management to prevent environmental contamination.

Regulatory Framework Governing Exploration Well Drilling

The regulatory landscape governing exploration well drilling varies considerably depending on geographic location. Generally, national and regional environmental protection agencies establish stringent regulations to minimize environmental impacts. These regulations often cover aspects such as permitting requirements, waste management protocols, air emission standards, spill prevention and response plans, and site restoration procedures. For example, in the United States, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) play significant roles in overseeing onshore drilling activities, while the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) regulates offshore operations.

Similar regulatory bodies exist in other countries, each with its own specific rules and enforcement mechanisms. Compliance with these regulations is crucial, and non-compliance can lead to substantial penalties.

Exploration wells are crucial for understanding subsurface geology, but designing the ideal home above ground can be equally challenging. Luckily, you can simplify the process significantly by learning how to use AI to design your dream home online for free, check out this helpful guide: how to use AI to design my dream home online for free.

Once you’ve perfected your above-ground design, you can focus on the more complex task of interpreting the data from your exploration well.

Mitigation Measures to Minimize Environmental Risks

Numerous mitigation measures are implemented to reduce the environmental footprint of exploration well drilling. These include the use of environmentally friendly drilling fluids, advanced spill prevention technologies, efficient waste management systems, and rigorous monitoring programs to detect and address potential environmental problems. Careful site selection to minimize habitat disturbance, erosion control measures, and the implementation of best practices for noise reduction are also crucial.

Remediation plans are developed in advance to address potential spills or other incidents, outlining specific steps to clean up contamination and restore the affected environment. Regular environmental audits and reporting requirements help ensure ongoing compliance with regulations and identify areas for improvement.

Potential Environmental Hazard and Remediation Strategies: Hydrocarbon Spills

A significant potential environmental hazard associated with exploration wells is the accidental release of hydrocarbons into the environment. This can occur due to well control failures, equipment malfunctions, or pipeline leaks. The consequences of such spills can be devastating, impacting soil and water quality, harming wildlife, and potentially affecting human health. Remediation strategies for hydrocarbon spills involve several steps, including immediate containment and cleanup efforts to prevent further spread.

This might involve the use of booms and skimmers to recover spilled oil from water bodies, or the excavation of contaminated soil. Bioremediation techniques, using microorganisms to break down hydrocarbons, can be employed for in-situ cleanup. Soil washing or other physical/chemical treatments might also be necessary. The extent and duration of remediation efforts depend on the severity and nature of the spill, as well as the specific environmental conditions of the affected area.

Post-remediation monitoring is essential to verify the effectiveness of the cleanup and ensure long-term environmental protection.

Exploration wells are crucial for discovering new resources, much like designing a home is a crucial step in creating a comfortable living space. Planning your dream home can be significantly easier with the help of AI powered home design software that integrates with smart home tech , allowing for precise control and efficient planning. Just as exploration wells require careful planning, so too does building your perfect smart home.

Economic Aspects of Exploration Wells

Exploration wells, while crucial for discovering new oil and gas reserves, represent a significant financial undertaking. The inherent risk associated with exploration—the possibility of finding nothing commercially viable—makes understanding the economic factors paramount for any oil and gas company. This section delves into the cost structure, influencing factors, and potential return on investment associated with these ventures.

Cost Components of Exploration Wells

Drilling and testing exploration wells involves substantial upfront capital expenditure. Costs vary significantly depending on factors such as location (onshore vs. offshore), well depth, geological complexity, and required technology. Major cost components include permitting and regulatory fees, site preparation, rig mobilization and operation, drilling fluids and equipment, logging and formation evaluation services, well testing, and finally, plugging and abandoning the well if unsuccessful.

Offshore wells, for instance, are considerably more expensive due to the added complexities and specialized equipment needed for operating in a marine environment. Deepwater wells can cost tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars.

Factors Influencing Economic Viability

Several factors interplay to determine the economic viability of an exploration well. These include the estimated size and quality of the potential reservoir, the prevailing oil and gas prices, the cost of drilling and testing, the geological risk (the probability of finding hydrocarbons), and the applicable tax regime and royalty payments. A high-risk, high-reward prospect in an area with a proven geological play might be deemed economically viable even with a high drilling cost, while a low-risk prospect with a small potential reserve might not be pursued due to low potential returns despite a lower drilling cost.

Accurate geological modeling and risk assessment are crucial for making informed decisions.

Return on Investment (ROI) for Successful and Unsuccessful Wells

The ROI for exploration wells dramatically differs between successful and unsuccessful ventures. A successful well that discovers a commercially viable hydrocarbon reservoir can yield exceptionally high returns, potentially generating billions of dollars in revenue over its lifespan. This high return is often necessary to offset the losses from numerous unsuccessful wells. Conversely, an unsuccessful well results in a complete loss of the significant investment made in drilling and testing.

The overall profitability of an exploration program hinges on the balance between successful and unsuccessful wells; a high success rate is essential for long-term financial health. For example, a company might drill ten exploration wells, with only one resulting in a commercially viable discovery. The success of that one well needs to generate sufficient revenue to compensate for the nine dry holes.

Exploration wells are crucial for discovering new resources, and the planning phase requires careful consideration. The cost of such projects can be significant, comparable to, or even exceeding, the expenses involved in designing a home, which is why understanding how much does it cost to use online AI home design software can offer a relatable perspective on large-scale project budgeting.

Ultimately, both exploration well planning and home design benefit from efficient resource allocation and careful cost analysis.

Impact of Oil and Gas Prices on Exploration Well Decisions

Oil and gas prices are a critical determinant in exploration well decisions. High commodity prices increase the profitability of successful wells, making even high-risk exploration ventures more attractive. Conversely, low prices significantly reduce the economic viability of exploration, leading to decreased exploration activity. Companies often delay or cancel exploration projects during periods of low prices, prioritizing the development of already discovered reserves.

The price volatility in the oil and gas market necessitates continuous monitoring and adjustment of exploration strategies. For instance, the sharp decline in oil prices in 2014-2016 resulted in a significant drop in global exploration activity, with many companies delaying or canceling projects until prices recovered.

Exploration wells are crucial for understanding subsurface geology, but planning the logistics can be complex. Designing efficient layouts for equipment and personnel is much easier with the help of top rated AI home design websites with easy user interfaces , which can create optimal space arrangements. These tools can then be adapted to streamline the exploration well site, ensuring safety and efficiency.

Case Studies of Exploration Wells

Exploration wells, by their very nature, are high-risk, high-reward endeavors. Analyzing both successful and unsuccessful examples provides invaluable insights into optimizing future exploration strategies and mitigating potential setbacks. The following case studies illustrate the diverse challenges and triumphs encountered in the search for hydrocarbons.

Successful Exploration Well: The Johan Sverdrup Field (North Sea)

The Johan Sverdrup field, located in the Norwegian sector of the North Sea, stands as a testament to successful exploration. The geological context is characterized by a thick Jurassic sandstone reservoir, situated beneath a complex overburden of shale and other sedimentary layers. Pre-drill seismic data indicated significant potential, but the precise reservoir extent and quality remained uncertain. The exploration well, drilled using advanced directional drilling techniques, encountered the reservoir as predicted, confirming its significant size and excellent reservoir properties (high porosity and permeability).

Extensive formation evaluation, including wireline logging and core analysis, provided crucial data for reservoir characterization. The results led to the development of a major oil field, significantly boosting Norway’s oil production. The success can be attributed to a combination of sophisticated seismic imaging, precise drilling execution, and thorough formation evaluation.

Unsuccessful Exploration Well: The BP Macondo Prospect (Gulf of Mexico)

The Deepwater Horizon oil spill, resulting from the Macondo prospect exploration well, serves as a stark reminder of the potential risks associated with deepwater drilling. The geological context involved a complex interplay of salt diapirs, faults, and high-pressure formations. While initial assessments suggested the presence of hydrocarbons, inadequate wellbore integrity and cementing procedures, coupled with insufficient pressure management, led to a catastrophic blowout.

The well’s failure highlighted the critical importance of rigorous risk assessment, adherence to safety protocols, and robust well control procedures in deepwater environments. The subsequent investigation revealed failures in communication, oversight, and a culture that prioritized speed over safety. The lessons learned emphasized the need for improved regulatory frameworks, enhanced technological advancements, and a fundamental shift in safety culture within the industry.

Comparison of Case Studies

| Feature | Johan Sverdrup | Macondo |

|---|---|---|

| Geological Setting | Relatively simple structure; thick Jurassic sandstone reservoir | Complex structure; salt diapirs, faults, high-pressure formations |

| Drilling Process | Advanced directional drilling; successful wellbore construction | Deepwater drilling; inadequate wellbore integrity and cementing; blowout |

| Results | Significant hydrocarbon discovery; major oil field development | Catastrophic blowout; environmental disaster; significant loss of life |

| Outcome | Highly successful; significant economic benefits | Complete failure; severe environmental and economic consequences |

Hypothetical Exploration Well: The “Phoenix” Prospect

The hypothetical “Phoenix” prospect is located in a rift basin setting, characterized by a series of interconnected fault blocks. The target reservoir is a fractured Paleozoic carbonate, situated at approximately 5,000 meters depth. The well encountered a sequence of overlying shales and sandstones before penetrating the carbonate reservoir. Initial logging data indicated the presence of significant porosity and permeability within the fractured zones, but fluid analysis revealed only limited hydrocarbon saturation.

Further analysis suggested that while the reservoir possessed good storage capacity, the lack of effective hydrocarbon migration pathways resulted in poor hydrocarbon accumulation. The well was ultimately deemed non-commercial, highlighting the importance of understanding not only reservoir properties but also the regional geological context and hydrocarbon migration history.

Closure

The exploration well process, while fraught with challenges and uncertainty, is a cornerstone of the energy industry. The high-stakes gamble of drilling an exploration well, with its potential for significant reward or devastating loss, highlights the crucial role of careful planning, advanced technology, and a deep understanding of geology. Each well drilled, whether successful or not, provides invaluable data that refines our understanding of the subsurface and guides future exploration efforts.

The lessons learned, both from triumphs and failures, constantly shape the evolution of exploration techniques, ensuring the continued search for vital energy resources.

Essential FAQs

What is the difference between a wildcat well and a step-out well?

A wildcat well is drilled in an entirely unexplored area with no prior production history. A step-out well is drilled some distance from a known producing well to test the lateral extent of the reservoir.

How long does it typically take to drill an exploration well?

The time required varies greatly depending on depth, location, and geological conditions. It can range from several weeks to several months.

What happens to an exploration well after testing?

If successful, it may be converted into a production well. If unsuccessful, it’s typically plugged and abandoned according to environmental regulations.

What are some common risks associated with exploration wells?

Risks include encountering unexpected geological formations, equipment malfunctions, environmental incidents, and ultimately, discovering no commercially viable hydrocarbons.

How is the environmental impact of exploration wells mitigated?

Mitigation strategies include careful planning, use of environmentally friendly drilling fluids, proper waste disposal, and adherence to strict regulatory guidelines.